Veterinary vaccines, when used in conjunction with other health measures, have proven to be powerful tools in the prevention, control, and even the elimination of animal diseases. PPR and dog-mediated rabies have been the focus of vaccination efforts worldwide. While most affected countries implement official vaccination to control these diseases, challenges such as improper use and poor quality of vaccines remain. The Global Animal Health Situation Report presented at WOAH’s 90th General Session describes the current situation and provides an analysis of these trends, based on the reporting of official vaccination by Members.

Implementing PPR vaccination in remote pastoral areas

PPR is a viral livestock disease that can decimate entire herds of sheep and goats. Today, it still threatens 80% of the world’s sheep and goat population. As a result, it puts at risk the livelihoods and food security of some 300 million rural families worldwide who rely on small ruminant production. Eradicating PPR through vaccination and other appropriate measures, would not only ensure animal health and welfare, but would also improve the living conditions farmers, many of whom are women.

From 2005 to 2022, an annual average of 70% of Members affected by PPR reported official vaccination against the disease. During the period 2005 – 2022, a stable trend was observed with a peak in 2015 (82% of affected Members).

Through the PRAPS project (Sahel Regional Project Supporting Pastoralism), six countries of the Sahel region, including Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Senegal, have been involved in an ambitious initiative to control PPR in the region. Notable achievements in PPR vaccination have been observed. Between 2016 and 2022, a staggering 188 million doses of PPR vaccine were distributed to the PRAPS countries and in 2022 alone, 32.2 million doses were delivered. The use of WOAH’s PPR vaccine bank has been instrumental to support the supply of large quantities of quality vaccines.

While significant progress has been made in PPR vaccination in the Sahel region, a number of challenges remain. Identifying small ruminants, ensuring the effectiveness of vaccinations, maintaining vaccine quality control, and addressing human resources constraints, including training and staffing shortages, pose significant hurdles to fully controlling the spread of PPR and achieving long-term control goals in the Sahel region. Lessons learnt are taken into account in the next phases of the project.

By addressing these challenges head-on, we can strive towards the global eradication of PPR, ensuring the protection of small ruminant populations, the livelihoods of farmers and the future of pastoralism.

Tackling rabies at the animal source

Besides livestock diseases, zoonoses are also on the radar for vaccination campaigns. Rabies, a deadly disease with a fatality rate of nearly 100% in both humans and animals, continues to pose a global threat, claiming the lives of approximately 59,000 people each year. Because dogs are the primary carriers of this devastating zoonotic disease, effective control and elimination of rabies requires tackling its root cause in animals. Dog-mediated rabies has therefore been a major focus of vaccination campaigns. From 2005 to 2022, an average of 78% of WOAH Members affected by rabies reported official vaccination of dogs against rabies. However, there has been a gradual decline in the percentage of countries implementing rabies control measures, dropping from 85% to 62% during the period.

To support the goal of zero human deaths from dog-mediated rabies and to keep track of the use of veterinary vaccines, the United Against Rabies Forum, hosted by WOAH on the behalf of the Tripartite, has developed a comprehensive document titled ‘Minimal Data Elements’, which serves as a vital resource for monitoring progress towards the ambitious Zero by 30 Global Strategic Plan. This document notably offers essential data elements for countries to collect and diligently submit to the World Health Organization (WHO) and WOAH. By harmonising data practices, countries can effectively contribute to the global fight against rabies and track advancements in vaccination coverage.

Boosting vaccination trends to better control animal diseases

WOAH has developed global strategies that have encouraged countries to implement vaccination programmes against PPR and dog-mediated rabies. Through these initiatives and strategic partnerships, WOAH provides technical expertise and guidance to its Members on the implementation of effective vaccination strategies. By disseminating knowledge, facilitating information sharing, and supporting countries in accessing vaccines through initiatives such as vaccine banks, WOAH has significantly contributed to improving disease control efforts worldwide. The implementation of disease global strategies also fosters collaboration among countries, encouraging them to tackle animal diseases collectively and safeguard both animal and human health.

It is imperative to take action together to prevent the spread of transboundary animal diseases and curb their effects on livelihoods and economies. Let’s work together to rid the world of dog-mediated rabies and PPR.

Over 500 million birds have died from avian influenza since 2005. The deadly bird disease has devastating consequences on the health of domestic and wild birds, as well as on biodiversity and livelihoods. Lately, the global spread of avian influenza has raised growing preoccupation with an unprecedented number of outbreaks reaching new geographical regions, unusual die-offs in wild birds, as well as an increasing number of cases in mammals. Despite countries’ efforts to implement surveillance as well as strict prevention and control measures—such as movement control, enhanced biosecurity, and stamping-out—avian influenza continues to spark concern among the international community.

Towards a paradigm shift in current avian influenza prevention and control measures?

The extent and severity of the situation requires the assessment of existing strategies to contain the disease and raises multiple questions. What are the gaps in current disease control strategies? How can they be better tailored to different contexts and settings? Do we need to rethink about the way we rear some poultry species? How can we ensure an early detection of outbreaks? Which complementary control options would be needed at country and regional level? Would the wider use of vaccination in birds be a sustainable solution? How can poultry and poultry products trade take place safely in the presence of vaccination? How to best optimise resources allocation?

To address the strategic questions and challenges that impede countries to progress towards the global control of the disease, WOAH will hold its first ever Animal Health Forum dedicated to discuss the topic on 22-23 May, in the framework of the 90th General Session. The Forum will introduce the Technical Item as a common thread and will provide one-of-a-kind chance to take stock of past and current strategies and explore other risk management options, more adapted to the current evolving situation. It will also be a unique opportunity to agree on suitable, science-based alternatives for disease surveillance and control, that can reduce the impact of the disease.

New concerns arise as the disease evolves

These past years, an unprecedented and broader range of virus strains has emerged, leading to further evolution of the viruses and thus creating an epidemiologically challenging landscape. Historically, the most severe form of the disease in poultry, high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI), used to mostly spread from farm to farm, while its low pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI) used to mainly circulate among wild birds, often remaining asymptomatic in these bird populations. Nowadays, we observe a persistent threat of HPAI encroaching into wild birds, which can carry the disease viruses over long distances and across country borders. Avian influenza has therefore spread rapidly to new regions, in particular in Central and South America where the disease had not been detected for 20 years. In this region, 10 countries reported the disease to WOAH. Whereas, at global level, 74 countries and territories have notified avian influenza outbreaks since October 2021; this wide geographical spread has no previous historical context.

Beyond the increased number of cases identified in poultry and wild birds in recent years, avian influenza is now being reported in wild and captive mammals. Recent cases in otters, foxes and mink have sparked animal and public health concerns pertaining to the risk of viruses becoming more adapted to mammals and what this means to humans.

Sporadic, but severe human cases have also occurred. Although transmission from birds to humans is rare and results from repeated exposure to infected birds, the risk of a pandemic remains.

Building an effective common response

Avian influenza is a serious threat to global health, livelihoods, food security, and biodiversity. While there have been significant efforts to prevent and control its spread, there is still much work to be done. The change of epidemiology of the disease these past two years has undermined the use of stamping-out as a main control measure. As we are looking for more sustainable production practices, we must explore collectively alternative methods of disease control, to prevent and mitigate the disease, and consequently, avoid destroying so many animals when food security is becoming a critical issue for many.

These strategic challenges will be extensively discussed during the upcoming Animal Health Forum on avian influenza. In particular, the topics of surveillance, disease control strategies, ways to ensure safe and fair international trade of poultry and poultry products and regional and global coordination will be debated.

These important discussions will result in the development of international recommendations and will provide a solid basis for the rehaul of the WOAH/FAO global strategy on high pathogenicity avian influenza developed under the umbrella of the GF-TADs.

We need to ensure that countries can respond to this major health threat under a common framework and that their governments are ready to mobilise sufficient resources to tackle avian influenza. Taking appropriate action will be critical to ensure, a safer, healthier future for everyone.

To follow the discussions, connect to our Animal Health forum:

Monday 22 May

- 9:00 a.m. – Session 1 – Avian influenza intelligence: Surveillance and monitoring for early detection and prevention

- 2:30 p.m. – Session 2 – Response: Disease control strategies for early response and business continuity. The role of vaccination

- 3:30 p.m. – Session 3 – Resilience: International standards to facilitate safe international trade

Tuesday 23 May

- 9:00 a.m. – Session 4 – Global coordinated strategy for the progressive control of avian influenza

More information

-

Avian influenza portal

-

Animal Health Forum

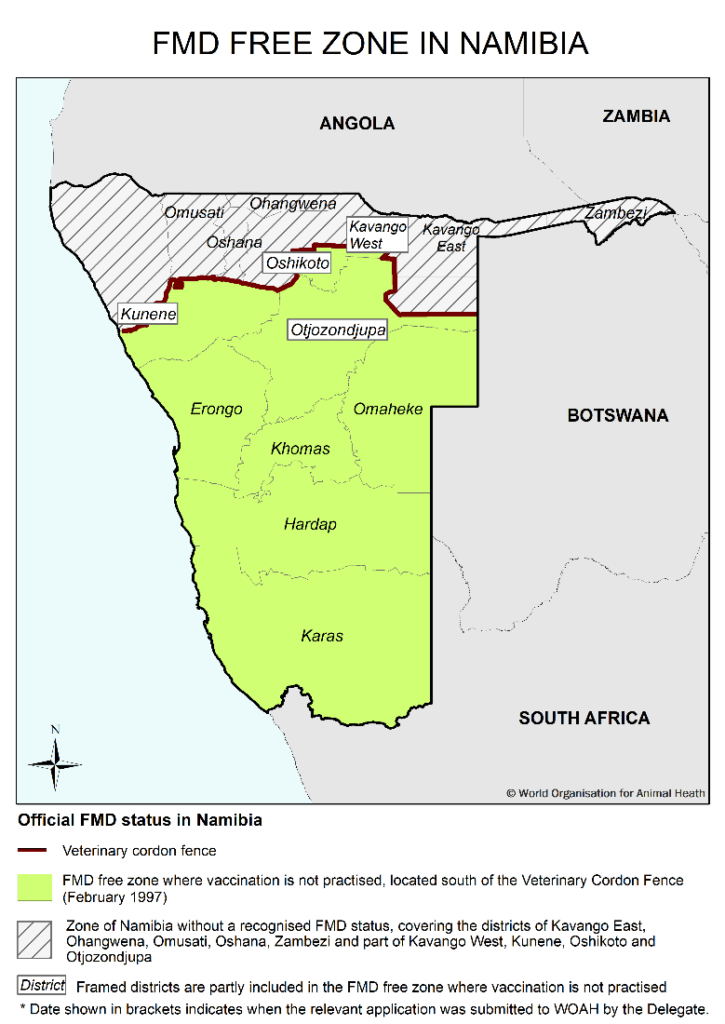

The development of Namibia is deeply rooted in the agricultural sector. With 90% of land suitable for livestock farming, a large proportion of the country’s rural population depends on this activity for food security, livelihoods and economic well-being. The estimated livestock population amounts to around 2 million cattle, 2,5 million sheep, 1,8 million goats and 17 thousand pigs. Animal production represents therefore a driver of economic growth, making key contributions to the local GDP.

Transboundary diseases such as FMD (foot and mouth disease) have the potential to dampen cross-border livestock trade and, more broadly, upend a country’s position within the global marketplace, making meat exports difficult. Worsened by drought, which affects rain-fed agriculture pushing pastoralists to seek more favourable areas for livestock grazing, an unforeseeably changing disease landscape has long put the economy of Namibia under strain.

The reliance on animal exports makes Namibia’s economy vulnerable to , whose outbreaks can result in severe production losses and lead to major halts to livestock trade. Preventing this disease, however, is possible through the implementation of effective sanitary measures aimed at preventing the introduction of the virus into the animal population. Early detection and response systems are equally important as they allow for an effective containment and eradication.

Namibia’s overall animal health situation is also shaped by its geographical position, sharing borders with countries and areas that are not free from FMD. Here, the movement of farmers grazing family cattle in areas where wild buffaloes may be present can occur, posing serious challenges to the control of transboundary animal diseases and the regulation of cross-border flows of goods. This movement has indeed led to outbreaks of both contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP) and FMD in animals returning to Namibia.

Keeping infectious diseases at bay

There are several ways to control endemic diseases. A zoning approach is one of them. Zoning is a provision explained in WOAH Standards, which allows a country to concentrate its resources in a defined restricted area where controlling and eradicating the disease would be achievable. A progressive extension of the free zone may lead to the eradication of the disease from the entire territory.

Achieving an official disease-free status nationwide should be the final goal for countries. However, given the difficulty of reaching such an objective, there are some undeniable benefits to establish and maintaining a subpopulation with a specific health status within a national territory, not only for disease prevention and control but also for the purposes of international trade.

FMD offered the first-ever opportunity for WOAH to set up a list of countries to be officially recognised as free of the disease, either in their entirety or in defined zones. Having implemented zoning since 1994, Namibia was one of the first countries to be granted an FMD free zone without vaccination status in 1997. Moreover, Namibia has been able to successfully secure and maintain the FMD free zone since this official recognition by WOAH, despite the outbreaks that have continued to unfold in the rest of the country.

The benefits of WOAH Standards for international trade

Dr Anja Boshoff-De Witt works at the national Meat Board, a regulating body that facilitates the export of livestock, meat and processed meat products in Namibia. She believes that translating animal health standards into real-world action can help build transformative solutions that will improve livelihoods and alleviate poverty.

The implementation of WOAH International Standards in Namibia has been providing a much-needed support to the economic growth. Namibia is export-oriented, which makes it essential for the country to comply with these recommendations.

Dr Anja Boshoff-De Witt, Manager Meat Standards at Meat Board of Namibia

WOAH Standards constitute a common language to achieve understanding and trust between countries. Their implementation along the production and supply chain is essential to develop national assurance systems minimising the potential risks associated with traded commodities posed to human or animal life or health in importing countries.

As a concrete example, demonstrating FMD-freedom based on International Standards and the official recognition of its status by the Organisation has facilitated the negotiations of Namibia with trading partners that are interested in livestock and meat, also enhancing a relationship of mutual trust. By implementing these Standards, Namibia has made rapid strides towards better animal health and safe livestock trade. Namibia’s beef exports have expanded to the European Union, Norway, People’s Republic of China, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. Livestock producers settled in the FMD-free zone have also seen new perspectives arise: the possibility to access the international market and thus to obtain higher prices for their livestock is a great incentive to enhance the livelihood of their families.

Livestock from the ‘FMD Infected and Protection zones’ may not move to the FMD free zone in Namibia. Livestock products may be moved from these zones to the free zone if prepared/processed in accordance with WOAH Standards. This includes the implementation of commodity-based trade for the movement of fresh beef.

Today, Namibia is well on its way to positioning itself in the global meat marketplace. The country ranks 29th and 35th of the top beef exporting countries for fresh and frozen beef respectively, and it supplies 1.4% of global sheep and goat exports. It was also the first in the African continent to tap into the lucrative US market, after it sent 25 tonnes of beef to Philadelphia in early 2020.

Looking forward, Namibia is set to further use the standards to improve animal health and facilitate safe international trade. A major goal is to enhance the animal health situation in areas still at-risk of FMD – either addressing the problem posed by its porous border or establishing more zones that can gain freedom from FMD.

In 2015, Namibia experienced one of its worst FMD outbreaks in the protection zone, which took nearly a year and $13 million to eradicate. WOAH Standards on zoning have helped address the outbreak and get the country back on its feet. The event offers both a lesson and a cautionary tale: animal health standards help address animal health challenges, unlocking economic potential and access to trade thereby securing a better future for everyone. Adapting them to national legislations and investing in their implementation hold key to a country’s boosted health situation and trade status.

Animal diseases: their impact on society

If a family in Madagascar loses a Zebu cow to disease, they are deprived of more than just the value of the animal. Cattle are often a lifeline for their owners. By providing milk for the household and working to plough fields and pull carts, they become an intimate part of family life. Animal diseases can also have ripple effects on trade, food supply, livelihoods and, ultimately, human health and well-being. Whilst these effects can be difficult to quantify, it is important to conduct this analysis so that we can address the needs of livestock keepers appropriately.

Therefore, the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, founded as OIE) has partnered with the University of Liverpool (UoL) to promote the development of knowledge in animal health economics. The ultimate goal is to help Veterinary and Aquatic Animal Health Services have the greatest impact on people’s lives and national economies.

In 2021, WOAH and its partners have secured more than 7 million US dollars to roll-out the Global Burden of Animal Diseases (GBADs) programme. Through GBADs, we strive to understand both the direct and indirect costs of animal diseases in order to improve not only animal health and welfare but also human well-being, particularly in rural, agriculture-based communities. The burden includes effects on livestock populations and agriculture, costs of mitigation efforts and trader impacts.

“The GBADs programme will help Veterinary Services improve their investments in the strengthening of animal health systems, their allocation of resources, and also have a data structure so that they can evaluate past policies” explains Jonathan Rushton, Director of the Global Burden of Animal Diseases programme, based at the University of Liverpool, United Kingdom.

Worldwide, 1,3 billion people depend on animals for their living

Each year, an estimated 300 billion USD is lost to animal diseases in livestock

Bringing together economic science and veterinary knowledge

To date, estimates of the overall “burden” of animal diseases has proven limited due to a lack of a systematic and standardised process across countries and animal production systems. How do animal diseases affect human health and well-being? What are the positive socioeconomic consequences of implementing preventative measures over time? Answers can come only by merging knowledge from veterinary and economic sciences.

“If we know what we’re losing or what we’re spending, then we’ll have a fairly good idea to present business cases for investment from either governments, the private sector, or individual farmers” explains Jonathan Rushton, who is also a professor of animal health and food systems economics at the University of Liverpool. “It’s about investing in the right places to achieve best outcomes on managing risk”.

The GBADs programme is led by WOAH jointly with the University of Liverpool and implemented by organisations and universities that work at the crossroads of public policy, private sector, and academia.

This year, the programme has entered into a new phase. We have rolled out a framework on measuring animal health burdens, their impacts on human lives and economies, and begun a case study in Ethiopia. A second case study, in Indonesia, was also launched in addition to a knowledge engine prototype to test the tools that will provide us with relevant data in the future. Building on these achievements, we aim to publish initial estimates of animal diseases burdens at global and national levels in 2022.

In May 2021, we also launched our first Collaborating Centre for the Economics of Animal Health, bringing together the University of Liverpool, Utrecht University, and the Norwegian Veterinary Institute. This collaboration will facilitate data collection using a standardised and analytical approach. It will also support the development of capacities on animal health economics and similar centres of excellence in other regions of the world.

Animal health for better human development and well-being

Livestock and aquatic animals provide roughly 1.3 billion of the global population with income, nutritious food, clothing, fertilizer, building materials and traction power. Poor animal health also correlates with poverty and malnutrition. Furthermore, it directly impacts women in rural agriculture-based economies, who comprise two-thirds of low-income livestock keepers. Linking existing animal disease data to socioeconomic consequences, GBADs programme will identify how animal health impacts small household income, the empowerment of women, and the equitable provision of a safe, affordable, and nutritious diet.

The approach that merges the animal health and socioeconomic sectors is on track to guide our actions on the long-term. The data collected by the GBADs programme will ultimately contribute to more efficient animal production systems. It will also help all stakeholders identify the most devastating animal health issues to address in order to prevent ripple effects on livelihoods and the well-being of both humans and animals.

Learn more about the GBADs programme here.

Funding for the GBADs programme: the Australian government, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Brooke, European Union – DG SANTE, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Ireland, Italian Ministry of Health, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office, and the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

An article from the 2021 Annual report: read the original

Monkeypox has become the star of recent health news, affecting over 16,000 people in at least 75 countries around the world. Like many other diseases, such as COVID-19 which affected 23 different animal species, monkeypox could cross the species barrier and jump to domestic and wild animals, putting everyone’s health at risk. At the World Organisation for Animal Health, our mission is to improve animal health globally. As monkeypox endangers us all, we must insist on why and how precautions should be taken to reduce the risk of transmission to animals.

Although the current outbreak of monkeypox is driven by human-to-human contact, the disease is known to be of animal origin and can therefore be passed on to certain species. Various wild mammals have been identified as susceptible to the monkeypox virus, such as rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, dormice and non-human primates. While some of these species exhibit signs and symptoms of the disease, others might not show any external or visible signs, which makes it more challenging to identify spillover events.

Very recently, monkeypox was detected in a dog most likely as a result of human to animal transmission following close direct contact with its owners who were symptomatic with the disease. This was the first documented case of human to animal transmission of the virus. We must remain vigilant. In case of further spillback of the virus from infected humans to animals, new animal reservoirs could be established, and the virus could become endemic in new geographic areas, heightening future risks for public health as well.

The World Organisation for Animal Health is closely monitoring the situation, in coordination with its experts because the heightened prevalence in humans may increase the risk of transmission to animals, and affect the epidemiology of the disease.

Dr Monique Eloit, Director General at the World Organisation for Animal Health

Viral transmission from humans to animals is a possibility that we need to further investigate to understand how likely this is to happen. All settings where we interact closely with animals, like zoos, wildlife rehabilitation facilities, hiking trails or at home with our pets, can facilitate the virus jumping from us to them. The monkeypox virus can enter the body through skin lesions (even those invisible to the naked eye), respiratory tracts, or mucous membranes.

A few (and simple!) precautions must therefore be taken. Always ensure that all waste, including medical waste, is safely disposed of and made inaccessible to rodent or other scavenger animals. And, if you are suspected or confirmed to be infected with the monkeypox virus, you should avoid all direct contact with animals, including livestock, wildlife, and even your pets.

We all need to be cautious. Monkeypox is yet another example of how human and animal health are interconnected. Only with strong multi-sectoral collaboration between public health experts, veterinarians, and wildlife authorities can we tackle diseases such as monkeypox, and ensure a safe future for us all.

Life underwater is sensitive to the changes the world is going through. Just as with terrestrial animals, the emergence of new diseases is placing significant stress on aquatic animal populations and the ecosystems they live in. This phenomenon is not likely to stop anytime soon, driven by factors such as climate change and unregulated trade.

Diseases can have severe consequences on the sustainable development of aquatic animal systems and on food security. Moreover, they can result in fewer aquatic animal products going to market, with more than a third of them being traded internationally. In a world where 50 million people depend on fisheries and aquaculture for their livelihoods, controlling aquatic animal diseases continues to be critical.

With this goal in mind, the World Organisation for Animal Health launched its global Aquatic Animal Health Strategy in 2021. As part of the roll-out plan of this strategy, the Organisation provides national Aquatic Animal Health Services with recommendations to enhance the surveillance of aquatic animal diseases. Surveillance aims to identify and manage risks associated with aquatic animal diseases, which can have an impact on the production and trade of aquatic animal products. It is a key preliminary step to ensure early detection and response to the occurrence of aquatic animal disease and for the country to progressively gain the capacity to claim freedom from a disease. Such achievement can support countries to meet trade requirements and facilitate the safe exchange of aquatic animals and their products.

The World Organisation for Animal Health encourages its Members to implement the surveillance recommendations provided in the Aquatic Code and Manual, to report any relevant disease events in a transparent and timely fashion, and to publish self-declarations of disease freedom. At the 89th General Session of the Organisation, the World Assembly of Delegates adopted a revised version of the Standard on aquatic animal disease surveillance, with the aim of guiding Members through the process of self-declaring freedom from an aquatic animal disease using solid evidence.

Aquaculture is recognised as the fastest-growing food production sector worldwide, with nearly 50% of the global supply of aquatic animals and products derived from it. This means that aquatic animal production increasingly contributes to human nutrition, poverty alleviation and sustainable development. A global authority working across borders to improve animal health, the World Organisation for Animal Health urges countries to implement its International Standards. As the world population and food demand continue to grow, building better surveillance will contribute to ensure improved aquatic animal health worldwide and to protect the health of life underwater.

Learn more

-

Self-declarations

-

Aquatic Animal Health Code

-

Aquatic animal health portal

According to the latest estimates, the global dog population exceeds 700 million individuals, of which 75% are roaming freely – meaning that they escape human supervision. Whether they belong to a household or a community, or assist farmers with livestock keeping, a large number of dogs can be found wandering outdoors. In many areas around the globe, dogs hold a special place: they are part of society. Even when they do not have an owner, dogs are frequently fed by people and children play with them, exposing themselves to potential bites. Nearly 99% of rabies cases in humans are attributed to dog bites and unfortunately, free-roaming dogs contribute to sustaining the presence of the disease in many countries. Rabies can be prevented if tackled at its main animal source: dogs. Vaccinating them is the most efficient way to eliminate the disease. Yet catching dogs, especially those who are prowling around inhabited areas, can prove quite challenging.

Running dog population management alongside rabies control efforts

Dog population management is a key pillar of a successful rabies control strategy. This multi-faceted approach encompasses measures that aim to enhance the health and welfare of dogs and mitigate the public health and safety issues that they cause to society. Some measures can also seek to influence dog population dynamics when necessary. In the framework of rabies control and elimination, it is a prerequisite to ensure that a sufficient amount of dogs is vaccinated to obtain immunity at population-level.

Without any doubt, vaccinating at least 70% of the dog population in at-risk areas, amongst other relevant measures, will take us to eliminating dog-mediated rabies. Mass dog vaccination is indeed one of the underpinning principles of the Global Strategic Plan to end human deaths from dog-mediated rabies by 2030, which fosters a One Health approach.

To support countries in achieving better vaccination coverage in dog populations, the Standard on dog population management (Chapter 7.7, formerly ‘stray dog population control’) has been recently updated, to cover all dogs, whether owned or unowned.

Handling free-roaming dogs

The management of dog populations helps ensure that every dog has access to veterinary care, thereby increasing the proportion of vaccinated animals.

In settings where the majority of free-roaming dogs targeted for vaccination are unowned, the “Catch, Neuter, Vaccinate, Return” approach is another key aspect which is likely to have a significant impact.

Neutering prevents the birth of unwanted dogs that will likely be abandoned and thus be unvaccinated, leading to poorer vaccination coverage.

Furthermore, this approach also benefits animal welfare, improving the life expectancy of vaccinated dogs. When applied, these measures can avoid resorting to the mass culling of dogs, often carried out without respecting animal welfare recommendation.

It is important to note that management interventions such as these need to be tailored appropriately to the local context. “There are different types of dogs, to which different interventions are going to work” reminds Dr Elly Hiby, Director at the International Companion Animal Management coalition (ICAM) and Chairwoman of the ad hoc Group on the revision of the dog population management Standard. It is paramount to understand the dynamics of dog populations in a given place and community attitudes towards them in order to determine which tools would be the most successful and work in the long run.

Looking at the dog population of tomorrow

Dog population management requires long-term efforts and not just a punctual set of actions. Dealing with the current canine population alone is not a sustainable solution. The origin of the next generation of free-roaming dogs must be understood to help maintain a high vaccination coverage.

Dr Elly Hiby insists that “owned dogs are a really significant source of the future free-roaming dog populations”. Therefore, making dog owners accountable for their animals and their potential offspring is critical, through legislation, education programmes and behaviour change communications. To promote responsible dog ownership, the World Organisation for Animal Health has implemented a regional awareness campaign in the Balkans as part of the WOAH Platform on animal welfare for Europe, with a number of tools, such as posters and leaflets for dog owners, as well as playbooks for kids. Engaging owners and/or community carers is a key step to ease the vaccination process, keeping in mind the objective of herd immunity.

A complex but necessary response

Having to deal with many factors at the same time, dog population management represents a multi-sectoral challenge, and requires the use of a comprehensive approach. All countries need to assess their dog demographics, take into consideration community involvement and attitudes and build long-term national strategies.

Investing time and resources in dog population management undeniably supports the end of rabies, by helping obtain a high vaccination coverage amongst the root causes of the transmission to humans. Around 59,000 fatalities could be avoided every year, and this approach is a steppingstone towards our common goal of zero human rabies deaths by 2030.

Learn more

-

Global Strategic Plan to end human deaths from rabies

-

Rabies

18 million tons, that is the weight of chicken eggs produced every year worldwide. Largely consumed for their protein intake, eggs are produced in sufficient quantities to meet the demand of all inhabitants of the planet and, very importantly, are available at a relatively cheap price compared to meat. However, their average cost has been rising lately, specifically in Europe and in North America, where production costs have risen dramatically, and millions of laying hens have been infected with avian influenza since last October.

For every inhabitant in the world, there is a laying hen producing eggs: we have enough to go around.

Ben Dellaert, Chairman of the avian influenza expert group, International Egg Commission (IEC)

According to the European Commission, egg prices have soared by around 22% in Europe and by 44% in the USA, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), compared to last year. Increased costs throughout the supply chain and the current lessened availability of feed and grains directly affected this rise in prices. However, avian influenza, or bird flu, has also played an undeniable part in this phenomenon in those regions, according to Ben Dellaert, from the International Egg Commission (IEC).

Bird flu is a severe viral disease that mainly affects poultry and wild birds, often causing death among flocks and leading to devastating socioeconomic impacts. Since October 2021, over 21 million cases in poultry were reported to the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, founded as OIE) in several regions of the world. Compared to previous years, this significant number is higher, and more birds have died.

Once bird flu hits a poultry farm, the disease can very easily spread among birds, and actions must be taken to mitigate its rapid transmission. One of the main containment measures is to cull birds that are infected but also healthy ones that are at risk of acquiring the disease, because of potential direct or indirect contact with infected birds. This year, some outbreaks have led to the culling of thousands of birds. For example, the Netherlands reported 33,000 cases of bird flu and, in order to mitigate its spread, over 2 million domesticated birds were put to death. This inevitably affects the egg production capacity. High mortality among laying hens, whether due to the disease itself or the culling measures, has a direct consequence on the number of eggs that can be produced. Looking closer at the USA’s case, the country has now lost 25 million laying hens, reducing their total egg production by 8%. This drop in production capacity causes a financial loss for egg producers, thus leading to a rise in egg prices.

As they are often the first group affected by this issue, we need to reflect on the impacts this type of disease has on farmers. While it is normal to consider the financial effects on farmers as they suffer a decrease in their activity and income due to the impact of avian influenza on their flock, there are secondary effects too. Ben Dellaert from IEC reminds us of the additional emotional impact:

When your animals die of this disease, and you have to get rid of them, it’s always a terrible thing to experience for the farmer.

Ben Dallert, Chairman of the avian influenza expert group, International Egg Commission (IEC)

Furthermore, when your farm has not yet been infected with bird flu, you also live with this constant threat that it might get to your birds.

Besides eggs, we can also expect other commodities, like poultry meat, to become less available and more expensive for the same reasons. This situation shows us that animal diseases, such as bird flu, can disrupt livelihoods and economies and threaten food security worldwide. Putting in place prevention measures, such as setting up appropriate surveillance and enhancing biosecurity in farms, is therefore key to avoid further negative impacts.

Paris, 20 April 2022 – Amongst the many challenges facing animal health, preventing animal diseases is a core mission of the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). Immunising animals against diseases and delivering quality vaccines, when vaccines exist, is the best preventive method to stop their spread. Vaccination has even led to the full eradication of Rinderpest, once a deadly livestock disease. Well aware of the severe health and socio-economic consequences animal diseases can have, the OIE, along with partners and donors, has made a goal to deliver high-quality animal vaccines to countries in need, by setting up vaccine banks.

As the old saying goes, prevention is better than a cure. This could not be truer, as we have to tackle several animal disease epidemics throughout the world, with devastating impacts, not only on animal health, but also on livelihoods, food security, international trade, and sometimes on human health. Vaccine-preventable diseases such as rabies, peste des petits ruminants (PPR) or foot and mouth disease (FMD) can be contained since we have a tool to stop them: vaccination.

Animal vaccination against the main livestock diseases is used with the aim of fighting diseases to improve the living conditions of breeders, supply the population with animal products and fight against poverty.

Dr Idriss Oumar Alfaroukh, PRAPS Coordinator

However, implementing effective animal vaccination campaigns can be challenging. Having the resources to purchase and deliver quality vaccines, sometimes in remote areas, while respecting storage and transportation factors to keep the vaccines properties, can be difficult.

This is why the OIE, with the support of donors and partners, has set up vaccine banks for several diseases. Since the creation of its first vaccine bank to control avian influenza in 2006, the OIE has helped its Members in addressing several animal diseases. The OIE vaccine banks allow the delivery of high-quality vaccines complying with OIE International Standards in a timely manner and at a pre-established low and fixed price. Because vaccines are dispatched safely and rapidly, the beneficiary countries can focus on other essential aspects of their national disease strategies, such as raising awareness, training vaccinators or improving biosecurity measures, etc.

As of December 2021, the OIE vaccine banks have enabled the delivery of a significant amount of doses against rabies, FMD and PPR.

In 2021, the FMD vaccine bank was closed. As of January 2022, the rabies and PPR vaccine banks remain active.

For more information on how our vaccine banks work, you can visit our website.

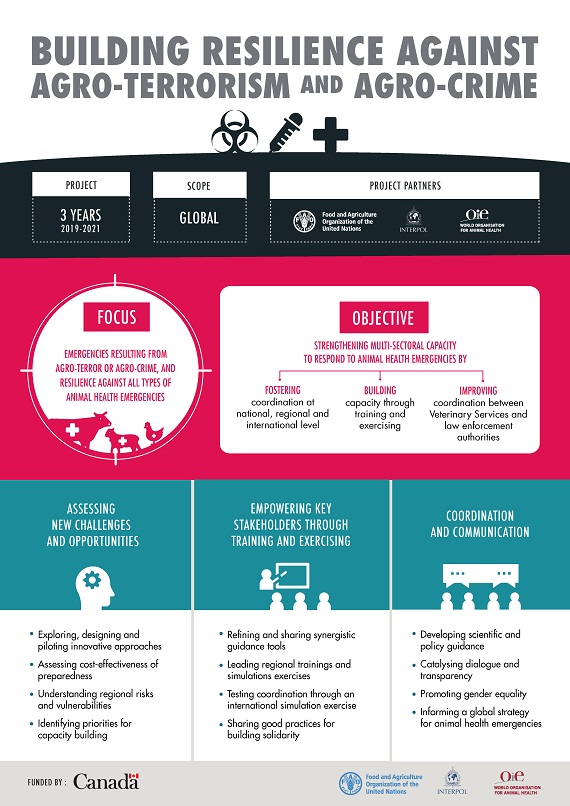

The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) are partners in an international project to build sustainable global resilience against animal health emergencies caused by agro-terrorism and agro-crime.

Established in October 2018, the project aims to foster coordination at the national, regional, and international levels. It focuses on regions where the previous work of the three organisations has identified gaps in various aspects of emergency management that may make countries vulnerable to agro-crime and agro-terrorism. The target regions include the Middle East, North Africa and South-East Asia. However, while the project concentrates on these regions, its outputs will be relevant to all countries worldwide.

To ensure that the resulting capacity building is fit for purpose, the project is currently assessing the global situation for emergency management by identifying areas that are vulnerable to agro-crime and agro-terrorism; understanding the cost-effectiveness of investing in preparedness; and using OIE, FAO and INTERPOL tools to examine emergency management, including the relationship between the law enforcement and veterinary sectors.

Based on this evidence, the project team is designing tools, workshops, and simulation exercises to pilot in the target regions. Training will include workshops on the principles of emergency management, including how to design, deliver and learn from a simulation exercise, how to write a contingency plan, and how to command and control the situation during an agro-terrorism event. To test capacity at the national and regional levels, tabletop simulation exercises will be held, based on an agro-crime or agro-terrorism scenario. All activities will include participants from both the law enforcement and veterinary sectors.

These activities will culminate in an international simulation exercise to test coordination and communication at the national level (of selected countries), as well as at the regional and international levels. The exercise will be designed around the response to an agro-terrorism scenario in which law enforcement and veterinary sectors must cooperate.

Finally, a Global Conference on Emergency Management will be held at the end of the project to showcase the project’s activities to a large multisectoral and interdisciplinary audience. The project partners hope to rally support from the international community to adopt an all-hazards approach to animal health emergencies; promote the inclusion of Veterinary Services in whole-of-government emergency and disaster frameworks by enhancing coordination between the law enforcement and veterinary sectors; and to foster a much stronger international emergency management network.

Thanks to the Weapons Threat Reduction Program (WTRP) of Global Affairs Canada for supporting this project.

An article from the OIE Bulletin: read the original