Terrestrial Animal Health Code

Terrestrial Animal Health Code |

Transport of animals by sea

Preamble: these recommendations apply to the following live domesticated animals: cattle, buffaloes, deer, camelids, sheep, goats, pigs and equines. They may also be applicable to other domesticated animals.

The amount of time animals spend on a journey should be kept to the minimum.

Animal behaviour

Animal handlers should be experienced and competent in handling and moving farm livestock and understand the behaviour patterns of animals and the underlying principles necessary to carry out their tasks.

The behaviour of individual animals or groups of animals will vary depending on their breed, sex, temperament and age and the way in which they have been reared and handled. Despite these differences, the following behaviour patterns, which are always present to some degree in domestic animals, should be taken into consideration in handling and moving the animals.

Most domestic livestock are kept in herds and follow a leader by instinct.

Animals which are likely to be hostile to others in a group situation should not be mixed.

The desire of some animals to control their personal space should be taken into account in designing loading and unloading facilities, transport vessels and containers.

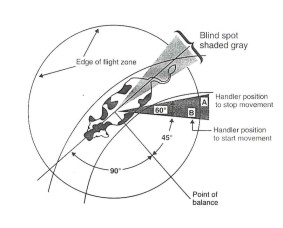

Domestic animals will try to escape if any person approaches closer than a certain distance. This critical distance, which defines the flight zone, varies among species and individuals of the same species, and depends upon previous contact with humans. Animals reared in close proximity to humans (i.e. tame) have a smaller flight zone, whereas those kept in free range or extensive systems may have flight zones which may vary from one metre to many metres. Animal handlers should avoid sudden penetration of the flight zone which may cause a panic reaction which could lead to aggression or attempted escape and compromise the welfare of the animals.

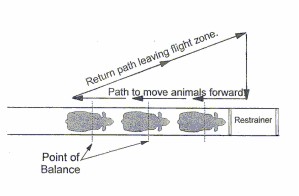

Animal handlers should use the point of balance at the animal’s shoulder to move animals, adopting a position behind the point of balance to move an animal forward and in front of the point of balance to move it backward.

Domestic animals have a wide-angle vision but only have a limited forward binocular vision and poor perception of depth. This means that they can detect objects and movements beside and behind them, but can only judge distances directly ahead.

Domestic animals can hear over a greater range of frequencies than humans and are more sensitive to higher frequencies. They tend to be alarmed by constant loud noises and by sudden noises, which may cause them to panic. Sensitivity to such noises should also be taken into account when handling animals.

Distractions and their removal

Design of new loading and unloading facilities or modification of existing facilities should aim to minimise the potential for distractions that may cause approaching animals to stop, baulk or turn back. Below are examples of common distractions and methods for eliminating them:

reflections on shiny metal or wet floors – move a lamp or change lighting;

dark entrances – illuminate with indirect lighting which does not shine directly into the eyes of approaching animals;

animals seeing moving people or equipment up ahead – install solid sides on chutes and races or install shields;

dead ends – avoid if possible by curving the passage, or make an illusory passage;

chains or other loose objects hanging in chutes or on fences – remove them;

uneven floors or a sudden drop in floor levels – avoid uneven floor surfaces or install a solid false floor to provide an illusion of a solid and continuous walking surface;

sounds of air hissing from pneumatic equipment – install silencers or use hydraulic equipment or vent high pressure to the external environment using flexible hosing;

clanging and banging of metal objects – install rubber stops on gates and other devices to reduce metal to metal contact;

air currents from fans or air curtains blowing into the face of animals – redirect or reposition equipment.

An example of a flight zone (cattle)

Handler movement pattern to move cattle forward

Responsibilities

Once the decision to transport the animals by sea has been made, the welfare of the animals during their journey is the paramount consideration and is the joint responsibility of all people involved. The individual responsibilities of persons involved will be described in more detail in this article. These recommendations may also be applied to the transport of animals by water within a country.

The management of animals at post-discharge facilities is outside the scope of this chapter.

General considerations

Exporters, importers, owners of animals, business or buying/selling agents, shipping companies, masters of vessels and managers of facilities are jointly responsible for the general health of the animals and their fitness for the journey, and for their overall welfare during the journey, regardless of whether duties are subcontracted to other parties during transport.

Exporters, shipping companies, business or buying/selling agents, and masters of vessels are jointly responsible for planning the journey to ensure the care of the animals, including:

choosing appropriate vessels and ensuring that animal handlers are available to care for the animals;

developing and keeping up-to-date contingency plans to address emergencies (including adverse weather conditions) and minimise stress during transport;

correct loading of the ship, provision of appropriate food, water, ventilation and protection from adverse weather, regular inspections during the journey and for appropriate responses to problems arising;

disposal of carcasses in accordance with international law.

To carry out the above mentioned responsibilities, the parties involved should be competent regarding transport regulations, equipment usage, and the humane handling and care of animals.

Specific considerations

The responsibilities of the exporters include:

the organisation, carrying out and completion of the journey, regardless of whether duties are subcontracted to other parties during transport;

ensuring that equipment and medication are provided as appropriate for the species and the journey;

securing the presence of the appropriate number of animal handlers competent for the species being transported;

ensuring compliance of the animals with any required veterinary certification, and their fitness to travel;

in case of animals for export, ensuring compliance with any requirements of the importing and exporting countries.

The responsibilities of the owners of the animals include the selection of animals that are fit to travel based on veterinary recommendations.

The responsibilities of the business or buying/selling agent include:

The responsibilities of masters of vessels include the provision of suitable premises for animals on the vessel.

The responsibilities of managers of facilities during loading include:

providing suitable premises for loading the animals;

providing an appropriate number of animal handlers to load the animals with minimum stress and the avoidance of injury;

minimising the opportunities for disease transmission while the animals are in the facilities;

providing appropriate facilities for emergencies;

providing facilities, veterinarians or animal handlers capable of killing animals humanely when required.

The responsibilities of managers of facilities during unloading include:

providing suitable facilities for unloading the animals onto transport vehicles for immediate movement or securely holding the animals in lairage, with shelter, water and feed, when required, for transit;

providing animal handlers to unload the animals with minimum stress and injury;

minimising the opportunities for disease transmission while the animals are in the facilities;

providing appropriate facilities for emergencies;

providing facilities, and veterinarians or animal handlers capable of killing animals humanely when required.

The responsibilities of the animal handlers include humane handling and care of the animals, especially during loading and unloading.

The responsibilities of the Competent Authority of the exporting country include:

establishing minimum standards for animal welfare, including requirements for inspection of animals before and during their travel, and for certification and record keeping;

approving facilities, containers, vehicles and vessels for the holding and transport of animals;

setting competence standards for animal handlers and managers of facilities;

implementation of the standards, including through accreditation of / interaction with other organisations and Competent Authorities;

monitor and evaluate health and welfare of the animals at the point of loading.

The responsibilities of the Competent Authority of the importing country include:

establishing minimum standards for animal welfare, including requirements for inspection of animals after their travel, and for certification and record keeping;

approve facilities, containers, vehicles and vessels for the holding and transport of animals;

setting competence standards for animal handlers and managers of facilities;

implementation of the standards, including through accreditation of / interaction with other organisations and Competent Authorities;

ensuring that the exporting country is aware of the required standards for the vessel transporting the animals;

monitor and evaluate health and welfare of the animals at the point of unloading;

give animal consignments priority to allow import procedures to be completed without unnecessary delay.

The responsibilities of veterinarians or in the absence of a veterinarian, the animal handlers travelling on the vessel with the animals include:

The receiving Competent Authority should report back to the sending Competent Authority on significant animal welfare problems which occurred during the journey.

Competence

All people responsible for animals during journeys should be competent to carry out the relevant responsibilities listed in Article 7.2.3. Competence in areas other than animal welfare would need to be addressed separately. Competence may be gained through formal training and/or practical experience.

The assessment of competence of animal handlers should at a minimum address knowledge, and ability to apply that knowledge, in the following areas:

planning a journey, including appropriate space allowance, feed, water and ventilation requirements;

responsibilities for the welfare of animals during the journey, including loading and unloading;

sources of advice and assistance;

animal behaviour, general signs of disease, and indicators of poor animal welfare such as stress, pain and fatigue, and their alleviation;

assessment of fitness to travel; if fitness to travel is in doubt, the animal should be examined by a veterinarian;

relevant authorities and applicable transport regulations, and associated documentation requirements;

general disease prevention procedures, including cleaning and disinfection;

appropriate methods of animal handling during transport and associated activities such as assembling, loading and unloading;

methods of inspecting animals, managing situations frequently encountered during transport such as adverse weather conditions, and dealing with emergencies, including euthanasia;

species-specific aspects and age-specific aspects of animal handling and care, including feeding, watering and inspection; and

maintaining a journey log and other records.

Assessment of competence for exporters should at a minimum address knowledge, and ability to apply that knowledge, in the following areas:

planning a journey, including appropriate space allowances, and feed, water and ventilation requirements;

relevant authorities and applicable transport regulations, and associated documentation requirements;

appropriate methods of animal handling during transport and associated activities such as cleaning and disinfection, assembling, loading and unloading;

species-specific aspects of animal handling and care, including appropriate equipment and medication;

sources of advice and assistance;

appropriate record keeping; and

managing situations frequently encountered during transport, such as adverse weather conditions, and dealing with emergencies.

Planning the journey

General considerations

Adequate planning is a key factor affecting the welfare of animals during a journey.

Before the journey starts, plans should be made in relation to:

preparation of animals for the journey;

type of transport vessel required;

route, taking into account distance, expected weather and sea conditions;

nature and duration of journey;

daily care and management of the animals, including the appropriate number of animal handlers, to help ensure the health and welfare of all the animals;

avoiding the mixing of animals from different sources in a single pen group;

provision of appropriate equipment and medication for the numbers and species carried; and

emergency response procedures.

Preparation of animals for the journey

When animals are to be provided with a novel diet or unfamiliar methods of supplying of feed or water, they should be preconditioned.

There should be planning for water and feed availability during the journey. Feed should be of appropriate quality and composition for the species, age, condition of the animals, etc.

Extreme weather conditions are hazards for animals undergoing transport and require appropriate vessel design to minimise risks. Special precautions should be taken for animals that have not been acclimatised or which are unsuited to either hot or cold conditions. In some extreme conditions of heat or cold, animals should not be transported at all.

Animals more accustomed to contact with humans and with being handled are likely to be less fearful of being loaded and transported. Animals should be handled and loaded in a manner that reduces their fearfulness and improves their approachability.

Behaviour-modifying (such as tranquillisers) or other medication should not be used routinely during transport. Such medicines should only be administered when a problem exists in an individual animal, and should be administered by a veterinarian or other person who has been instructed in their use by a veterinarian. Treated animals should be placed in a dedicated area.

Control of disease

As animal transport is often a significant factor in the spread of infectious diseases, journey planning should take into account the following:

When possible and agreed by the Veterinary Authority of the importing country, animals should be vaccinated against diseases to which they are likely to be exposed at their destination.

Medications used prophylactically or therapeutically should only be administered by a veterinarian or other person who has been instructed in their use by a veterinarian.

Mixing of animals from different sources in a single consignment should be minimized.

Vessel and container design and maintenance

Vessels used for the sea transport of animals should be designed, constructed and fitted as appropriate to the species, size and weight of the animals to be transported. Special attention should be paid to the avoidance of injury to animals through the use of secure smooth fittings free from sharp protrusions and the provision of non-slippery flooring. The avoidance of injury to animal handlers while carrying out their responsibilities should be emphasised.

Vessels should be properly illuminated to allow animals to be observed and inspected.

Vessels should be designed to permit thorough cleaning and disinfection, and the management of faeces and urine.

Vessels and their fittings should be maintained in good mechanical and structural conditions.

Vessels should have adequate ventilation to meet variations in climate and the thermo-regulatory needs of the animal species being transported. The ventilation system should be effective when the vessel is stationary. An emergency power supply should be available to maintain ventilation in the case of primary machinery breakdown.

The feeding and watering system should be designed to permit adequate access to feed and water appropriate to the species, size and weight of the animals, and to minimise soiling of pens.

Vessels should be designed so that the faeces or urine from animals on upper levels do not soil animals on lower levels, or their feed or water.

Loading and stowage of feed and bedding should be carried out in such a way to ensure protection from fire hazards, the elements and sea water.

Where appropriate, suitable bedding, such as straw or sawdust, should be added to vessel floors to assist absorption of urine and faeces, provide better footing for animals and protect animals (especially young animals) from hard or rough flooring surfaces and adverse weather conditions.

The above principles apply also to containers used for the transport of animals.

Special provisions for transport in road vehicles on roll-on/roll-off vessels or for containers

Road vehicles and containers should be equipped with a sufficient number of adequately designed, positioned and maintained securing points enabling them to be securely fastened to the vessel.

Road vehicles and containers should be secured to the ship before the start of the sea journey to prevent them being displaced by the motion of the vessel.

Vessels should have adequate ventilation to meet variations in climate and the thermo-regulatory needs of the animal species being transported, especially where the animals are transported in a secondary vehicle/container on enclosed decks.

Due to the risk of limited airflow on certain decks of a vessel, a road vehicle or container may require a forced ventilation system of greater capacity than that provided by natural ventilation.

Nature and duration of the journey

The maximum duration of a journey should be determined taking into account factors that determine the overall welfare of animals, such as:

the ability of the animals to cope with the stress of transport (such as very young, old, lactating or pregnant animals);

the previous transport experience of the animals;

the likely onset of fatigue;

the need for special attention;

the need for feed and water;

the increased susceptibility to injury and disease;

space allowance and vessel design;

weather conditions;

vessel type used, method of propulsion and risks associated with particular sea conditions.

Space allowance

The number of animals which should be transported on a vessel and their allocation to different pens on the vessel should be determined before loading.

The amount of space required, including headroom, depends on the species of animal and should allow the necessary thermoregulation. Each animal should be able to assume its natural position for transport (including during loading and unloading) without coming into contact with the roof or upper deck of the vessel. When animals lie down, there should be enough space for every animal to adopt a normal lying posture.

Calculations for the space allowance for each animal should be carried out in reference to a relevant national or international document. The size of pens will affect the number of animals in each.

The same principles apply when animals are transported in containers.

Ability to observe animals during the

journey

Animals should be positioned to enable each animal

to be observed regularly and clearly by an animal handler or other

responsible person, during the journey to ensure

their safety and good welfare.

Emergency response procedures

There should be an emergency management plan that identifies the important adverse events that may be encountered during the journey, the procedures for managing each event and the action to be taken in an emergency. For each important event, the plan should document the actions to be undertaken and the responsibilities of all parties involved, including communications and record keeping.

Documentation

Animals should not be loaded

until the documentation required to that point is complete.

The documentation accompanying the consignment

should include:

journey travel

plan and emergency management plan;

time, date and place of loading;

the journey log – a

daily record of inspection and important events which includes records

of morbidity and mortality and actions taken, climatic conditions,

food and water consumed, medication provided, mechanical defects;

expected time, date and place of arrival

and unloading;

veterinary certification, when required;

animal identification to allow traceability of animals to the premises of departure, and, where possible, to the premises of origin;

details of any animals considered at particular risk of suffering poor welfare during transport (point 3 e) of Article 7.2.7.);

number of animal handlers on board, and their competencies; and

stocking density estimate for each load in the consignment.

When veterinary certification is required to accompany consignments of animals, it should address:

when required, details of disinfection carried out;

fitness of the animals to travel;

animal identification (description, number, etc.); and

health status including any tests, treatments and vaccinations carried out.

Pre-journey period

General considerations

Before each journey, vessels should be thoroughly cleaned and, if necessary, treated for animal and public health purposes, using chemicals approved by the Competent Authority. When cleaning is necessary during a journey, this should be carried out with the minimum of stress and risk to the animals.

In some circumstances, animals may require pre-journey assembly. In these circumstances, the following points should be considered:

Pre-journey rest is necessary if the welfare of the animals has become poor during the collection period because of the physical environment or the social behaviour of the animals.

When animals are to be provided with a novel diet or unfamiliar methods of supplying feed or water, they should be preconditioned.

Where an animal handler believes that there is a significant risk of disease among the animals to be loaded or significant doubt as to their fitness to travel, the animals should be examined by a veterinarian.

Pre-journey assembly / holding areas should be designed to:

securely contain the animals;

maintain an environment safe from hazards, including predators and disease;

protect animals from exposure to adverse weather conditions;

allow for maintenance of social groups; and

allow for rest, watering and feeding.

Selection of compatible groups

Compatible groups should be selected before transport to avoid adverse animal welfare consequences. The following recommendations should be applied when assembling groups of animals:

animals of different species should not be mixed unless they are judged to be compatible;

animals of the same species can be mixed unless there is a significant likelihood of aggression; aggressive individuals should be segregated (recommendations for specific species are described in detail in Article 7.2.12.). For some species, animals from different groups should not be mixed because poor welfare occurs unless they have established a social structure;

young or small animals may need to be separated from older or larger animals, with the exception of nursing mothers with young at foot;

animals with horns or antlers should not be mixed with animals lacking horns or antlers, unless judged to be compatible; and

animals reared together should be maintained as a group; animals with a strong social bond, such as a dam and offspring, should be transported together.

Fitness to travel

Animals should be inspected by a veterinarian or an animal handler to assess fitness to travel. If its fitness to travel is in doubt, it is the responsibility of a veterinarian to determine its ability to travel. Animals found unfit to travel should not be loaded onto a vessel.

Humane and effective arrangements should be made by the owner or agent for the handling and care of any animal rejected as unfit to travel.

Animals that are unfit to travel include, but may not be limited to:

those that are sick, injured, weak, disabled or fatigued;

those that are unable to stand unaided or bear weight on each leg;

those that are blind in both eyes;

those that cannot be moved without causing them additional suffering;

newborn with an unhealed navel;

females travelling without young which have given birth within the previous 48 hours;

pregnant animals which would be in the final 10% of their gestation period at the planned time of unloading;

animals with unhealed wounds from recent surgical procedures such as dehorning.

Risks during transport can be reduced by selecting animals best suited to the conditions of travel and those that are acclimatised to expected weather conditions.

Animals at particular risk of suffering poor welfare during transport and which require special conditions (such as in the design of facilities and vehicles, and the length of the journey) and additional attention during transport, may include:

very large or obese individuals;

very young or old animals;

excitable or aggressive animals;

animals subject to motion sickness;

animals which have had little contact with humans;

females in the last third of pregnancy or in heavy lactation.

Hair or wool length should be considered in relation to the weather conditions expected during transport.

Loading

Competent supervision

Loading should be carefully planned as it has the potential to be the cause of poor welfare in transported animals.

Loading should be supervised by the Competent Authority and conducted by animal handler(s). Animal handlers should ensure that animals are loaded quietly and without unnecessary noise, harassment or force, and that untrained assistants or spectators do not impede the process.

Facilities

The facilities for loading, including the collecting area at the wharf, races and loading ramps should be designed and constructed to take into account the needs and abilities of the animals with regard to dimensions, slopes, surfaces, absence of sharp projections, flooring, sides, etc.

Ventilation during loading and the journey should provide for fresh air, and the removal of excessive heat, humidity and noxious fumes (such as ammonia and carbon monoxide). Under warm and hot conditions, ventilation should allow for the adequate convective cooling of each animal. In some instances, adequate ventilation can be achieved by increasing the space allowance for animals.

Loading facilities should be properly illuminated to allow the animals to be easily inspected by animal handlers, and to allow the ease of movement of animals at all times. Facilities should provide uniform light levels directly over approaches to sorting pens, chutes, loading ramps, with brighter light levels inside vehicles/containers, in order to minimise baulking. Dim light levels may be advantageous for the catching of some animals. Artificial lighting may be required.

Goads and other aids

When moving animals, their species-specific behaviour should be used (see Article 7.2.12.). If goads and other aids are necessary, the following principles should apply:

Animals that have little or no room to move should not be subjected to physical force or goads and other aids which compel movement. Electric goads and prods should only be used in extreme cases and not on a routine basis to move animals. The use and the power output should be restricted to that necessary to assist movement of an animal and only when an animal has a clear path ahead to move. Goads and other aids should not be used repeatedly if the animal fails to respond or move. In such cases it should be investigated whether some physical or other impediment is preventing the animal from moving.

The use of such devices should be limited to battery-powered goads on the hindquarters of pigs and large ruminants, and never on sensitive areas such as the eyes, mouth, ears, anogenital region or belly. Such instruments should not be used on horses, sheep and goats of any age, or on calves or piglets.

Useful and permitted goads include panels, flags, plastic paddles, flappers (a length of cane with a short strap of leather or canvas attached), plastic bags and rattles; they should be used in a manner sufficient to encourage and direct movement of the animals without causing undue stress.

Painful procedures (including whipping, tail twisting, use of nose twitches, pressure on eyes, ears or external genitalia), or the use of goads or other aids which cause pain and suffering (including large sticks, sticks with sharp ends, lengths of metal piping, fencing wire or heavy leather belts), should not be used to move animals.

Excessive shouting at animals or making loud

noises (e.g. through the cracking of whips) to encourage them to

move should not occur as such actions may make the animals agitated,

leading to crowding or falling.

The use of well trained dogs to help with

the loading of

some species may be acceptable.

Animals should be grasped or lifted in a manner which avoids pain or suffering and physical damage (e.g. bruising, fractures, dislocations). In the case of quadrupeds, manual lifting by a person should only be used in young animals or small species, and in a manner appropriate to the species; grasping or lifting animals only by their wool, hair, feathers, feet, neck, ears, tails, head, horns, limbs causing pain or suffering should not be permitted, except in an emergency where animal welfare or human safety may otherwise be compromised.

Conscious animals should not be thrown, dragged

or dropped.

Performance standards should be established in which numerical scoring is used to evaluate the use of such instruments, and to measure the percentage of animals moved with an electric instrument and the percentage of animals slipping or falling as a result of their usage.

Travel

General considerations

Animal handler(s) should

check the consignment immediately before departure to ensure that

the animals have been loaded in accordance with the load plan. Each

consignment should be checked following any incident or situation

likely to affect their welfare and in any case within 12 hours of

departure.

If necessary and where possible adjustments

should be made to the stocking density as

appropriate during the journey.

Each pen of animals should be observed on a daily basis for normal behaviour, health and welfare, and the correct operation of ventilation, watering and feeding systems. There should also be a night patrol. Any necessary corrective action should be undertaken promptly.

Adequate access to suitable feed and water should be ensured for all animals in each pen.

Where cleaning or disinfestation is necessary during travel, it should be carried out with the minimum of stress to the animals.

Sick or injured animals

Sick or injured animals should be segregated.

Sick or injured animals should be appropriately treated or humanely killed, in accordance with a predetermined emergency response plan (Article 7.2.5.). Veterinary advice should be sought if necessary. All drugs and products should be used in accordance with recommendations from a veterinarian and in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

A record of treatments carried out and their outcomes should be kept.

When humane killing is necessary, the animal handler must ensure that it is carried out humanely. Recommendations for specific species are described in Chapter 7.6. Veterinary advice regarding the appropriateness of a particular method of euthanasia should be sought as necessary.

Unloading and post-journey handling

General considerations

The required facilities and the principles of animal handling detailed in Article 7.2.8. apply equally to unloading, but consideration should be given to the likelihood that the animals will be fatigued.

Unloading should be carefully planned as it has the potential to be the cause of poor welfare in transported animals.

A livestock vessel should have priority attention when arriving in port and have priority access to a berth with suitable unloading facilities. As soon as possible after the vessel’s arrival at the port and acceptance of the consignment by the Competent Authority, animals should be unloaded into appropriate facilities.

The accompanying veterinary certificate and other documents should meet the requirements of the importing country. The veterinary inspection should be completed as quickly as possible.

Unloading should be supervised by the Competent Authority and conducted by animal handler(s). The animal handlers should ensure that animals are unloaded as soon as possible after arrival but sufficient time should be allowed for unloading to proceed quietly and without unnecessary noise, harassment or force, and that untrained assistants or spectators do not impede the process.

Facilities

The facilities for unloading including the collecting area at the wharf, races and unloading ramps should be designed and constructed to take into account of the needs and abilities of the animals with regard to dimensions, slopes, surfaces, absence of sharp projections, flooring, sides, etc.

All unloading facilities should have sufficient lighting to allow the animals to be easily inspected by the animal handlers, and to allow ease of movement of animals at all times.

There should be facilities to provide animals with appropriate care and comfort, adequate space, access to quality feed and clean drinking water, and shelter from extreme weather conditions.

Sick or injured animals

An animal that has become sick, injured or disabled during a journey should be appropriately treated or humanely killed (see Chapter 7.6.). When necessary, veterinary advice should be sought in the care and treatment of these animals.

In some cases, where animals are non-ambulatory due to fatigue, injury or sickness, it may be in the best welfare interests of the animal to be treated or humanely killed aboard the vessel.

If unloading is in the best welfare interests of animals that are fatigued, injured or sick, there should be appropriate facilities and equipment for the humane unloading of such animals. These animals should be unloaded in a manner that causes the least amount of suffering. After unloading, separate pens and other appropriate facilities and treatments should be provided for sick or injured animals.

Cleaning and disinfection

Vessels and containers used to carry the animals should be cleaned before re-use through the physical removal of manure and bedding, by scraping, washing and flushing vessels and containers with water until visibly clean. This should be followed by disinfection when there are concerns about disease transmission.

Manure, litter and bedding should be disposed of in such a way as to prevent the transmission of disease and in compliance with all relevant health and environmental legislation.

Actions in the event of a refusal to allow the importation of a shipment

The welfare of the animals should be the first consideration in the event of a refusal to import.

When animals have been refused import, the Competent Authority of the importing country should make available suitable isolation facilities to allow the unloading of animals from a vessel and their secure holding, without posing a risk to the health of the national herd, pending resolution of the situation. In this situation, the priorities should be:

The Competent Authority of the importing country should provide urgently in writing the reasons for the refusal.

In the event of a refusal for animal health reasons, the Competent Authority of the importing country should provide urgent access to a WOAH-appointed veterinarian(s) to assess the health status of the animals with regard to the concerns of the importing country, and the necessary facilities and approvals to expedite the required diagnostic testing.

The Competent Authority of the importing country should provide access to allow continued assessment of the ongoing health and welfare situation.

If the matter cannot be promptly resolved,

the Competent Authorities of

the exporting and importing countries should

call on WOAH to mediate.

In the event that the animals are required to remain on the vessel, the priorities should be:

The Competent Authority of the importing country should allow provisioning of the vessel with water and feed as necessary.

The Competent Authority of the importing country should provide urgently in writing the reasons for the refusal.

In the event of a refusal for animal health reasons, the Competent Authority of the importing country should provide urgent access to a WOAH-appointed veterinarian(s) to assess the health status of the animals with regard to the concerns of the importing country, and the necessary facilities and approvals to expedite the required diagnostic testing.

The Competent Authority of the importing country should provide access to allow continued assessment of the ongoing health and other aspects of the welfare of the animals, and the necessary actions to deal with any issues which arise.

If the matter cannot be urgently resolved, the Competent Authorities of the exporting and importing countries should call on WOAH to mediate.

WOAH should utilise its informal procedure for dispute mediation to identify a mutually agreed solution which will address the animal health and welfare issues in a timely manner.

Species-specific issues

Camelids of the new world in this context comprise llamas, alpacas, guanaco and vicuna. They have good eyesight and, like sheep, can negotiate steep slopes, though ramps should be as shallow as possible. They load most easily in a bunch as a single animal will strive to rejoin the others. Whilst they are usually docile, they have an unnerving habit of spitting in self-defence. During transport, they usually lie down. They frequently extend their front legs forward when lying, so gaps below partitions should be high enough so that their legs are not trapped when the animals rise.

Cattle are sociable animals and may become agitated if they are singled out. Social order is usually established at about two years of age. When groups are mixed, social order has to be re-established and aggression may occur until a new order is established. Crowding of cattle may also increase aggression as the animals try to maintain personal space. Social behaviour varies with age, breed and sex; Bos indicus and B. indicus-cross animals are usually more temperamental than European breeds. Young bulls, when moved in groups, show a degree of playfulness (pushing and shoving) but become more aggressive and territorial with age. Adult bulls have a minimum personal space of six square metres. Cows with young calves can be very protective, and handling calves in the presence of their mothers can be dangerous. Cattle tend to avoid ’dead end’ in passages.

Goats should be handled calmly and are more easily led or driven than if they are excited. When goats are moved, their gregarious tendencies should be exploited. Activities which frighten, injure or cause agitation to animals should be avoided. Bullying is particularly serious in goats. Housing strange goats together could result in fatalities, either through physical violence, or subordinate goats being refused access to food and water.

Horses in this context include all solipeds, donkeys, mules, hinnies and zebra. They have good eyesight and a very wide angle of vision. They may have a history of loading resulting in good or bad experiences. Good training should result in easier loading, but some horses can prove difficult, especially if they are inexperienced or have associated loading with poor transport conditions. In these circumstances, two experienced animal handlers can load an animal by linking arms or using a strop below its rump. Blindfolding may even be considered. Ramps should be as shallow as possible. Steps are not usually a problem when horses mount a ramp, but they tend to jump a step when descending, so steps should be as low as possible. Horses benefit from being individually stalled, but may be transported in compatible groups. When horses are to travel in groups, their shoes should be removed.

Pigs have poor eyesight, and may move reluctantly in unfamiliar surroundings. They benefit from well-lit loading bays. Since they negotiate ramps with difficulty, these should be as level as possible and provided with secure footholds. Ideally, a hydraulic lift should be used for greater heights. Pigs also negotiate steps with difficulty. A good ’rule-of-thumb’ is that no step should be higher than the pig’s front knee. Serious aggression may result if unfamiliar animals are mixed. Pigs are highly susceptible to heat stress.

Sheep are sociable animals with good eyesight and tend to ’flock together’, especially when they are agitated. They should be handled calmly and their tendency to follow each other should be exploited when they are being moved. Sheep may become agitated if they are singled out for attention and will strive to rejoin the group. Activities which frighten, injure or cause agitation to sheep should be avoided. They can negotiate steep ramps.

nb: first adopted in 1998; most recent update adopted in 2008.

2024 ©OIE - Terrestrial Animal Health Code |